Climate model

- This article is about the theories and mathematics of climate modeling. For computer-driven prediction of Earth's climate, see Global climate model.

Climate models use quantitative methods to simulate the interactions of the atmosphere, oceans, land surface, and ice. They are used for a variety of purposes from study of the dynamics of the climate system to projections of future climate. The most talked-about use of climate models in recent years has been to project temperature changes resulting from increases in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases.

All climate models take account of incoming energy from the sun as short wave electromagnetic radiation, chiefly visible and short-wave (near) infrared, as well as outgoing energy as long wave (far) infrared electromagnetic radiation from the earth. Any imbalance results in a change in temperature.

Models can range from relatively simple to quite complex:

- A simple radiant heat transfer model that treats the earth as a single point and averages outgoing energy

- this can be expanded vertically (radiative-convective models), or horizontally

- finally, (coupled) atmosphere–ocean–sea ice global climate models discretise and solve the full equations for mass and energy transfer and radiant exchange.

This is not a full list; for example "box models" can be written to treat flows across and within ocean basins. Furthermore, other types of modelling can be interlinked, such as land use, allowing researchers to predict the interaction between climate and ecosystems.

Box models

Box models are simplified versions of complex systems, reducing them to boxes (or reservoirs) linked by fluxes. The boxes are assumed to be mixed homogeneously. Within a given box, the concentration of any chemical species is therefore uniform. However, the abundance of a species within a given box may vary as a function of time due to the input to (or loss from) the box or due to the production, consumption or decay of this species within the box.

Simple box models, i.e. box model with a small number of boxes whose properties (e.g. their volume) do not change with time, are often useful to derive analytical formulas describing the dynamics and steady-state abundance of a species. More complex box models are usually solved using numerical techniques.

Box models are used extensively to model environmental systems or ecosystems and in studies of ocean circulation and the carbon cycle.[1]

Zero-dimensional models

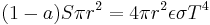

A very simple model of the radiative equilibrium of the Earth is

where

- the left hand side represents the incoming energy from the Sun

- the right hand side represents the outgoing energy from the Earth, calculated from the Stefan-Boltzmann law assuming a model-fictive temperature, T, sometimes called the 'equilibrium temperature of the Earth', that is to be found,

and

- S is the solar constant – the incoming solar radiation per unit area—about 1367 W·m−2

is the Earth's average albedo, measured to be 0.3.[2][3]

is the Earth's average albedo, measured to be 0.3.[2][3]- r is Earth's radius—approximately 6.371×106m

- π is the mathematical constant (3.141...)

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant—approximately 5.67×10−8 J·K−4·m−2·s−1

is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant—approximately 5.67×10−8 J·K−4·m−2·s−1 is the effective emissivity of earth, about 0.612

is the effective emissivity of earth, about 0.612

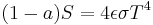

The constant πr2 can be factored out, giving

Solving for the temperature,

This yields an apparent effective average earth temperature of 288 K (15 °C; 59 °F).[4] This is because the above equation represents the effective radiative temperature of the Earth (including the clouds and atmosphere). The use of effective emissivity and albedo account for the greenhouse effect.

This very simple model is quite instructive, and the only model that could fit on a page. For example, it easily determines the effect on average earth temperature of changes in solar constant or change of albedo or effective earth emissivity. Using the simple formula, the percent change of the average amount of each parameter, considered independently, to cause a one degree Celsius change in steady-state average earth temperature is as follows:

- Solar constant 1.4%

- Albedo 3.3%

- Effective emissivity 1.4%

The average emissivity of the earth is readily estimated from available data. The emissivities of terrestrial surfaces are all in the range of 0.96 to 0.99[5][6] (except for some small desert areas which may be as low as 0.7). Clouds, however, which cover about half of the earth’s surface, have an average emissivity of about 0.5[7] (which must be reduced by the fourth power of the ratio of cloud absolute temperature to average earth absolute temperature) and an average cloud temperature of about 258 K (−15 °C; 5 °F).[8] Taking all this properly into account results in an effective earth emissivity of about 0.64 (earth average temperature 285 K (12 °C; 53 °F)).

This simple model readily determines the effect of changes in solar output or change of earth albedo or effective earth emissivity on average earth temperature. It says nothing, however about what might cause these things to change. Zero-dimensional models do not address the temperature distribution on the earth or the factors that move energy about the earth.

Radiative-convective models

The zero-dimensional model above, using the solar constant and given average earth temperature, determines the effective earth emissivity of long wave radiation emitted to space. This can be refined in the vertical to a zero-dimensional radiative-convective model, which considers two processes of energy transport:

- upwelling and downwelling radiative transfer through atmospheric layers that both absorb and emit infrared radiation

- upward transport of heat by convection (especially important in the lower troposphere).

The radiative-convective models have advantages over the simple model: they can determine the effects of varying greenhouse gas concentrations on effective emissivity and therefore the surface temperature. But added parameters are needed to determine local emissivity and albedo and address the factors that move energy about the earth.

Effect of ice-albedo feedback on global sensitivity in a one-dimensional radiative-convective climate model.[9][10][11]

Higher-dimension models

The zero-dimensional model may be expanded to consider the energy transported horizontally in the atmosphere. This kind of model may well be zonally averaged. This model has the advantage of allowing a rational dependence of local albedo and emissivity on temperature – the poles can be allowed to be icy and the equator warm – but the lack of true dynamics means that horizontal transports have to be specified.[12]

EMICs (Earth-system models of intermediate complexity)

Depending on the nature of questions asked and the pertinent time scales, there are, on the one extreme, conceptual, more inductive models, and, on the other extreme, general circulation models operating at the highest spatial and temporal resolution currently feasible. Models of intermediate complexity bridge the gap. One example is the Climber-3 model. Its atmosphere is a 2.5-dimensional statistical-dynamical model with 7.5° × 22.5° resolution and time step of half a day; the ocean is MOM-3 (Modular Ocean Model) with a 3.75° × 3.75° grid and 24 vertical levels.[13]

GCMs (global climate models or general circulation models)

Three (or more properly, four since time is also considered) dimensional GCM's discretise the equations for fluid motion and energy transfer and integrate these over time. They also contain parametrisations for processes—such as convection—that occur on scales too small to be resolved directly.

Atmospheric GCMs (AGCMs) model the atmosphere and impose sea surface temperatures as boundary conditions. Coupled atmosphere-ocean GCMs (AOGCMs, e.g. HadCM3, EdGCM, GFDL CM2.X, ARPEGE-Climat)[14] combine the two models. The first general circulation climate model that combined both oceanic and atmospheric processes was developed in the late 1960s at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory[15] AOGCMs represent the pinnacle of complexity in climate models and internalise as many processes as possible. However, they are still under development and uncertainties remain. They may be coupled to models of other processes, such as the carbon cycle, so as to better model feedback effects.

Most recent simulations show "plausible" agreement with the measured temperature anomalies over the past 150 years when forced by natural forcings alone, but better agreement is achieved when observed changes in greenhouse gases and aerosols are also included.[16][17]

Research and development

There are three major types of institution where climate models are developed, implemented and used:

- National meteorological services. Most national weather services have a climatology section.

- Universities. Relevant departments include atmospheric sciences, meteorology, climatology, and geography.

- National and international research laboratories. Examples include the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR, in Boulder, Colorado, USA), the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL, in Princeton, New Jersey, USA), the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research (in Exeter, UK), the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany, or the Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l'Environnement (LSCE), France, to name but a few.

The World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), hosted by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), coordinates research activities on climate modelling worldwide.

See also

- Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) (in the US)

- Climateprediction.net

- GFDL CM2.X

- Tropical cyclone prediction model

Climate models on the web

- Dapper/DChart — plot and download model data referenced by the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ccsm.ucar.edu — NCAR/UCAR Community Climate System Model (CCSM)

- climateprediction.net — do it yourself climate prediction

- giss.nasa.gov — the primary research GCM developed by NASA/GISS (Goddard Institute for Space Studies)

- edgcm.columbia.edu — the original NASA/GISS global climate model (GCM) with a user-friendly interface for PCs and Macs

- cccma.be.ec.gc.ca — CCCma model info and interface to retrieve model data

- nomads.gfdl.noaa.gov — NOAA / Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory CM2 global climate model info and model output data files

- climate.uvic.ca — University of Victoria Global climate model, free for download. Leading researcher was a contributing author to the recent IPCC report on climate change.

References

- ^ Sarmiento, J.L.; Toggweiler, J.R. (1984). "A new model for the role of the oceans in determining atmospheric P CO 2". Nature 308 (5960): 621–24. doi:10.1038/308621a0. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v308/n5960/abs/308621a0.html.

- ^ Goode, P. R.; et al. (2001). "Earthshine Observations of the Earth’s Reflectance". Geophys. Res. Lett. 28 (9): 1671–4. Bibcode 2001GeoRL..28.1671G. doi:10.1029/2000GL012580.

- ^ "Scientists Watch Dark Side of the Moon to Monitor Earth's Climate". American Geophysical Union. April 17, 2001. http://www.agu.org/sci_soc/prrl/prrl0113.html.

- ^ eospso.gsfc.nasa.gov

- ^ icess.ucsb.edu

- ^ Jin M, Liang S (15 June 2006). "An Improved Land Surface Emissivity Parameter for Land Surface Models Using Global Remote Sensing Observations". J. Climate 19 (12): 2867–81. doi:10.1175/JCLI3720.1. http://www.glue.umd.edu/~sliang/papers/Jin2006.emissivity.pdf.

- ^ T.R. Shippert, S.A. Clough, P.D. Brown, W.L. Smith, R.O. Knuteson, and S.A. Ackerman. "Spectral Cloud Emissivities from LBLRTM/AERI QME". Proceedings of the Eighth Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Science Team Meeting March 1998 Tucson, Arizona. http://www.arm.gov/publications/proceedings/conf08/extended_abs/shippert_tr.pdf.

- ^ A.G. Gorelik, V. Sterljadkin, E. Kadygrov, and A. Koldaev. "Microwave and IR Radiometry for Estimation of Atmospheric Radiation Balance and Sea Ice Formation". Proceedings of the Eleventh Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Science Team Meeting March 2001 Atlanta, Georgia. http://www.arm.gov/publications/proceedings/conf11/extended_abs/gorelik_ag.pdf.

- ^ pubs.giss.nasa.gov

- ^ Wang, W.C.; P.H. Stone (1980). "Effect of ice-albedo feedback on global sensitivity in a one-dimensional radiative-convective climate model". J. Atmos. Sci. 37: 545–52. Bibcode 1980JAtS...37..545W. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037<0545:EOIAFO>2.0.CO;2. http://pubs.giss.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/abstract.cgi?id=wa03100m. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ grida.no

- ^ shodor.org

- ^ pik-potsdam.de

- ^ cnrm.meteo.fr

- ^ celebrating200years.noaa.gov

- ^ "Climate Change 2001: Working Group I: The Scientific Basis". http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/figspm-4.htm.

- ^ "Web archive backup: Simulated global warming 1860–2000". http://web.archive.org/web/20060527001324/www.hadleycentre.gov.uk/research/hadleycentre/pubs/talks/sld017.html.

External links

- (IPCC 2001 section 8.3) — on model hierarchy

- (IPCC 2001 section 8) — much information on coupled GCM's

- Coupled Model Intercomparison Project

- On the Radiative and Dynamical Feedbacks over the Equatorial Pacific Cold Tongue

- Basic Radiation Calculations — The Discovery of Global Warming

- Henderson-Sellers, A.; Robinson, P. J. (1999). Contemporary Climatology. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-27631-4. http://www.pearsoned.co.uk/Bookshop/detail.asp?item=100000000002249.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

![T = \sqrt[4]{ \frac{(1-a)S}{4 \epsilon \sigma}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2b69ce089bc58ada665c65cb280d09be.png)